What’s news at Sounds Like Design?

The Sounds Like Design blog began in 2016 and since then we’ve covered business development and marketing topics, important policy and regulatory issues that affect the profession, and we’ve featured guest posts from several influential architects.

If you’d like to contribute to the blog about a topic or issue that you are passionate about, or think is important to share with your peers and colleagues, email us with your story idea, suggested images and proposed deadline, and we’ll collaborate to help you tell your story to a wider audience.

You can search the blog or sort posts by category

“Is your job getting easier or harder, over time?" - Peter Wood shares his perspective

Peter Wood weighs up the challenges that designers face in trying to balance clients’ changing expectations while navigating increasingly complex regulatory requirements. He offers suggestions about how slowing down can help to manage these challenges.

Transform your architecture practice with the 3P questions

How much do you know about the performance of your architecture practice, and whether your current business development and marketing activities are capable of generating a sustainable and profitable livelihood for you and your team members?

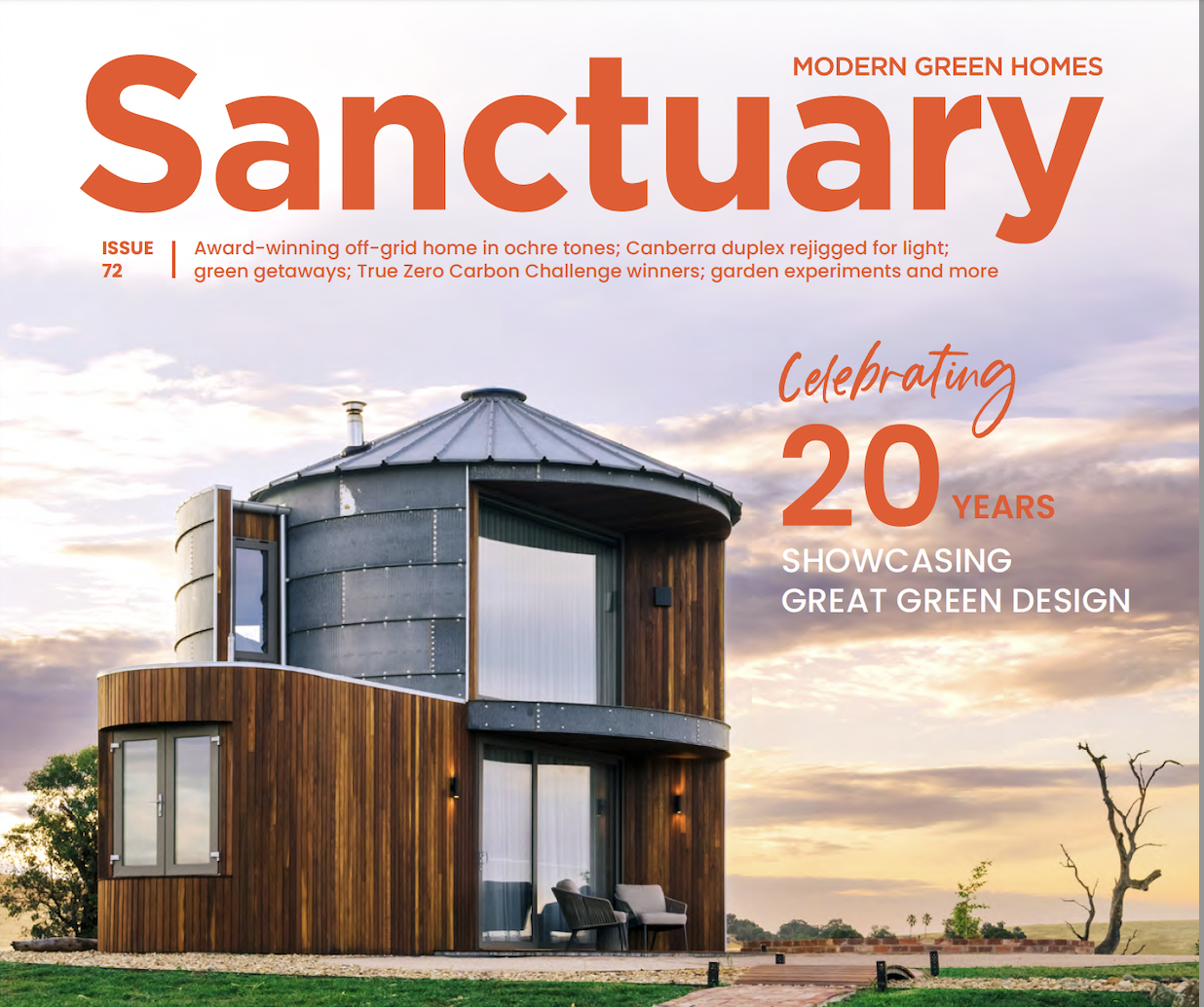

20 years of Sanctuary magazine: sustainable living with style

Sanctuary magazine is celebrating 20 years in 2025, and Rachael Bernstone has contributed stories to most issues since 2007. To mark this major anniversary, she was invited to reflect on her journey with the publication so far.

Frequently Asked Questions about the Shake + Stir Experiment

These are the FAQs that we’ve received from architects who want to learn more about our ground-breaking Shake + Stir Experiment. If you have a question that’s not covered here, you can email Rachael directly to ask.

8 reasons that architecture projects go off the rails (and how to keep them on track)

Your clients don’t realise how stressful, demanding and expensive working with an architect can be, and many projects get derailed along the way. So how can architects pre-empt common issues and proactively address them, to ensure more projects are successfully completed?

Why learning new comms and leadership skills is NOTHING like architecture school

Architects are leading the charge into new knowledge domains, and carry significant leadership responsibility.

Good leadership is characterised by an ability to combine data and storytelling in a way that inspires others to take action.

So how can architects upskill to meet the challenges facing the profession and society more broadly, in 2025 and beyond?

Are you scared of asking questions and looking silly?

This is part 3 of a series about how to overcome common struggles in architecture practices. In this article, Rachael Bernstone explores how a fear of asking questions can harm your career and practice, and she provides some suggestions to overcome it.

So you won an architecture award! What’s next?

The 2020 Architecture Awards ceremonies are almost complete, so how you can convert awards entries into marketing materials to promote your practice? Better still, how can you translate those entries - and any accolades you won - into new clients and projects?

Insights from an Experienced Senior Architect for younger architects

Boom-and-bust cycles are an inescapable part of being an architect. In this article, we share wisdom and insights - generously provided by an Experienced Senior Architect - for younger architects who might be experiencing their first economic downturn.

10 ways that your future clients are NOT like architects (and how to tailor your comms to enhance trust and connection…)

How are architects different from their future clients? Let us count the ways! This list sets out 10 key differences and provides suggestions about how architects can frame their marketing to attract and win more of the clients and projects you most love working on.

Is your “lack of time” preventing you from creating your future life and practice?

This is part 2 of a new series about how to overcome common struggles in architecture practices, where Rachael Bernstone unpacks and reframes her own "lack of time" for business development and marketing.

How to get over the fear of getting more visible in your architecture practice and career

This is part 1 of a new series about how to overcome common struggles in architecture practices, by business development and marketing expert - and good design advocate - Rachael Bernstone.

Can you help us gather market research insights?

Did you learn much about business development and marketing in your formal architecture studies? Share your thoughts, feedback and insights for a chance to win a free enrolment - for you and a friend - in Architecture Marketing 360.

Are you investing and upskilling in the right areas?

This blog post outlines some of the emerging key topics and issues from architects and provides resources to upskill and learn more - around AI and big tech, affordable housing, environmental sustainability and reporting, and well-being.

My pitch to the architecture profession

Architecture is undergoing a profound transformation - from client-as-patron to client-as-customer models – which presents new opportunities to make good design more accessible to more people.

Are you taking advantage of "persuasion windows" to grow architecture's market share pie?

This is Part 6 in the series on legal protections for the word “Architect” / architects’ salaries / well-being. It provides insights about how architects can take advantage of new "persuasion windows" to serve more clients, develop new services and grow architecture's share of the market pie.

How to report potential infringements of the protected title “architect” and its derivatives

This is Part 5 of the series that joins the dots between legal protections for the title architect, architects’ salaries and fees, and architects’ well-being. In this article, we look at how to report potential infringements, and whether that’s the best course of action for architects to take

What’s the magic bullet for architects?

This is Part 4 in the series on legal protections for the word “Architect” / architects’ salaries / well-being. It puts forward the magic bullet to help architects communicate the value of good design to clients and the wider community.

Feedback from readers and architects on the blog series about protected titles and architects’ salaries

This is Part 3 in the series on protected titles, architects' salaries, wellbeing and business development. It brings together feedback from across our community about the first two blog articles.

How do architects’ salaries compare?

Architects’ salaries are typically lower than many others in the construction sector, and doctors and lawyers who also complete five-year degrees This article compares salary survey stats and asks whether there might be a way to improve this situation, going forward.