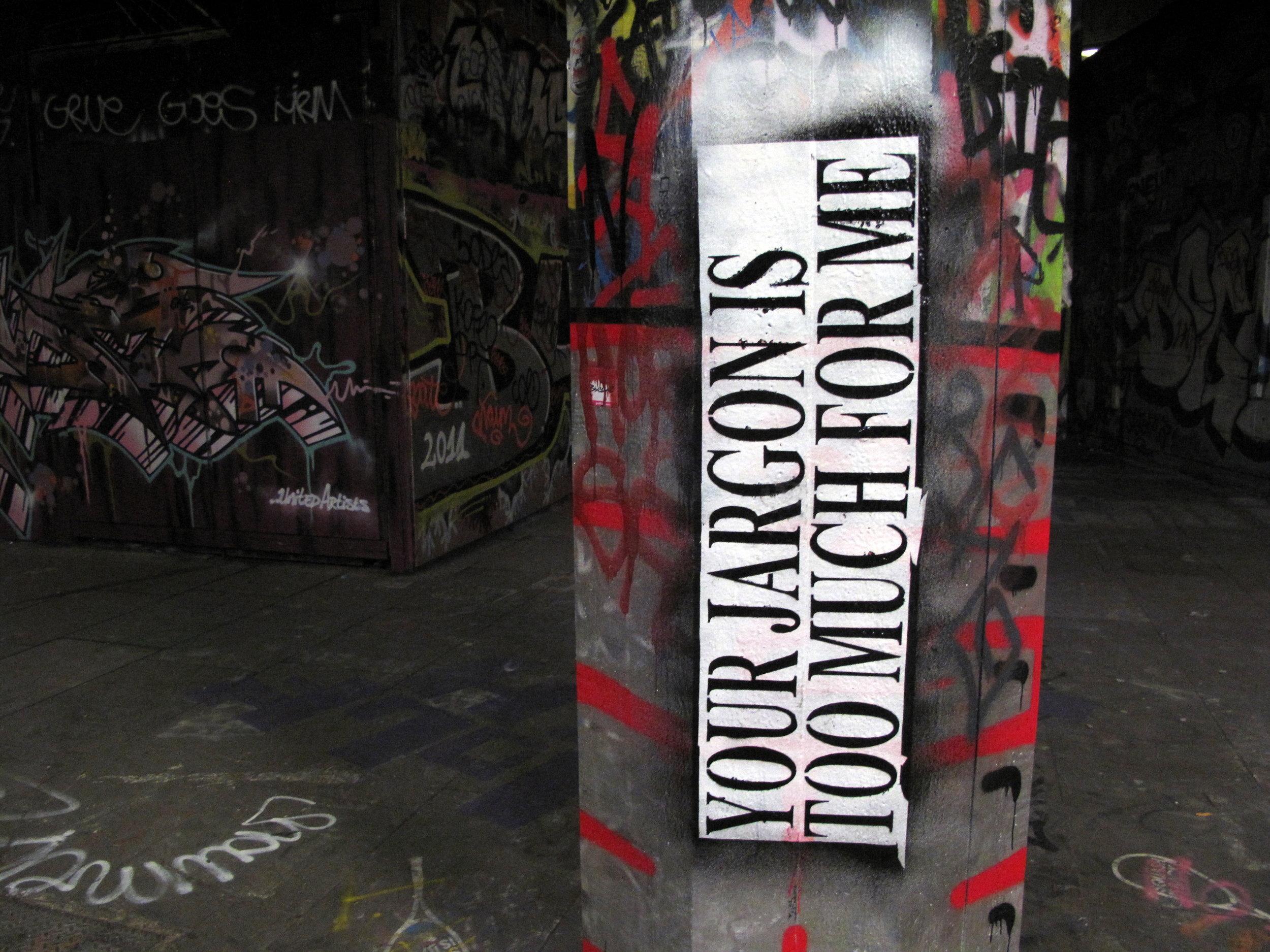

Architecture Marketing: Are you using accessible language in your practice communications?

Cantilever. Composition. Concept.

Massing. Materiality. Miesian.

Theory. Thermal mass. Threshold.

These are all words that architects use in everyday life.

When architects talk to – or write for – other architects, the use of architectural jargon, or 'archi-speak', is ok, because the audience understands it too. But trouble arises when architects talk to people who didn't study architecture (that's most of the population!), who don't realise that, for example, a cantilever is the “sticky out-y” bit of a building that provides balance and symmetry to the overall look and feel, as expressed in the original design idea.

Looking at the list at the top again: most people don’t get that the overall shape of glass and steel can produce a building that resembles a famous pavilion designed by a great German-American architect whose first name was Ludwig. Or, that the science that underpins passive solar design will be most keenly observed at the juncture between outside and inside, where the ground meets the floor. (These statements are not necessarily true, by the way, but you get my drift. Don’t you?)

When architects congregate and converse in the vernacular* of design – a language they were immersed in and mastered during those five long years at university – they reinforce the notion that this language is commonly spoken. And at conferences and awards ceremonies where architects gather with their peers, there are very few people in the room to question the superlatives that abound about spatial qualities and façade articulation.

What architects are prone to forgetting is that most people outside the profession – their clients, the building occupants, the general public – do not speak this hallowed language of design. Architects are thereby trapped in what writer and linguist Stephen Pinker calls ‘The Curse of Knowledge’. In his book The Sense of Style, Pinker asserts:

“The Curse of Knowledge is the single best explanation I know of why good people write bad prose. It simply doesn’t occur to the writer that her readers don’t know what she knows – that they haven’t mastered the patois of her guild, can’t divine the missing steps that seem too obvious to mention, have no way to visualise a scene that to her is as bright as day. And so she doesn’t bother to explain the jargon, or spell out the logic, of supply the necessary detail.”

Pinker adds that writers – and I would argue that architects are especially guilty of this – find it hard to put themselves in the position of the audience.

“When you’ve learned something so well that you forget that other people may not know it, you also forget to check whether they know it. Several studies have shown that people are not easily disabused of their curse of knowledge, even when they are told to keep the reader [or listener] in mind, to remember what it was like to learn something, or to ignore what they know.”

Pinker suggests that people who want to improve their writing skills (or architects who want to become better communicators) should avoid the use of jargon, abbreviations and technical vocabulary. That’s not going to be easy. Go back and re-read some of your architects statements or awards entries and see if you draw too richly on the language of ‘archi-speak’.

How would you strip back your prose or your presentation to make it more easily understood to a layperson? To revert to ‘arch-speak’ for a moment, to hammer home this point: how would you remove the unnecessary ornamentation so that your communication message is more Loos than Borromini?

For a start, I recommend you bookmark the link to ‘150 Weird Words That Only Architects Use’, compiled by contributors to ArchDaily.com. Each time you plan to write about a project, or prepare a submission for council planners, or craft a presentation for a developer, check the list, and eliminate as much of the ‘archi-speak’ as possible.

Then, do what Pinker suggests, and “close the loop”, or obtain a feedback signal:

“Show a draft to some people who are similar to [your] intended audience and find out whether they can follow it. This sounds banal, but is in fact profound.”

So, we can summarise Pinker’s expert advice into two key points:

Architects need to jettison the jargon, and abbreviations, and technical terms, in favour or language that’s more readily understood.

Then they need to check and recheck that their message is being received clearly and without confusion, by their intended audience.

Sounds easy, right? If your practice could use some help to make your communications more easily understood, Sounds Like Design is ready to assist. Our specialty is talking about architecture in plain language, and we produce all types of communications about design, including awards entries, submission documents, website text, and marketing and branding materials. Contact us directly to find out how SLD can help your business.

* Did you see what I did there?

This is Part 1 of the Sounds Like Design 'Comms Toolkit' series, which aims to help architects become better communicators. Sign up to receive weekly updates and more useful tips, or contact us directly to ask about our consulting services.

References:

Stephen Pinker, The Sense of Style, Penguin Random House, 2014.